2020 Labex Publication

“Gene flow among reproductively isolated species”

Dr Gianni Liti, a Labex SIGNALIFE project leader working on Population Genomics and Complex Traits, has just recently published in Nature a paper on how genomic introgressions occur among reproductively isolated yeast species

This publication involved Dr Liti’s research team at the Institute for Research on Cancer and Aging Nice (IRCAN) at The University Côte d’Azur, among them one Labex PhD student, Melania D’Angiolo as first author !!

D’Angiolo M, De Chiara M, Yue JX, Irizar A, Stenberg S, Persson K, Llored A, Barré B, Schacherer J, Marangoni R, Gilson E, Warringer J and Liti G. 2020. A yeast living ancestor reveals the origin of genomic introgressions. Nature. In press.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2889-1

English version

How can organisms whose DNA are so different that sex between them fails to create offspring, nevertheless exchange genes? This mystery has irked biologists for many years. We now disclose an unexpected mechanism that allows DNA exchange in absence of sex, helped by the lucky finding of a living yeast fossil with an ancient genome structure.

Lineages that become separated from each other, for example by migration, accumulate unique differences in their DNA, which are due to errors that occur when they copy their DNA. Lineages that encounter each other after having spent substantial time apart can nevertheless often engage in sex and produce hybrids with mixed DNA. Offspring from these hybrids, as they can find no other mates, typically cross back to one of the parent lineages, and beget children whose DNA is predominantly of one of the DNA types. After many generations of such backcrossings, only short scattered segments of the other DNA type, known as introgressions, remain. Non-African human populations carry 2% of Neanderthal DNA, as a result of ancient admixture and introgression. DNA introgressed from one species into another can have both positive and negative effects and these change over time. Some genes introgressed from Neanderthals have recently become a threat to human health as they increase the risk of COVID-19.

Mysteriously, we often find gene introgressions between species whose DNA are so different that sex fails to produce offspring. How is this possible? Evidently, the reproductive barriers have been penetrated, but how has long remained a conundrum. Common baker’s yeast, humans’ best friend that help us produce bread, beer, wine, spirits, coffee, cacao and many other products that are important to human wellbeing, is reproductively isolated from its wild sister species, the otherwise insipid Saccharomyces paradoxus. While the two yeasts can mate and form hybrids, their DNA differences (~12%) prevent them from exchanging DNA correctly and their offspring almost always die. Nevertheless, stretches of S. paradoxus DNA have invaded baker’s yeast genomes in a process resembling the introgression of Neanderthal DNA into non-African humans. How could these yeast DNA introgressions occur when the hybrid is sterile?

We stumbled across a clone of an ancestral yeast hybrid with a genome structure that is hundreds of thousands of generations old, i.e. a real living fossil. Curiously, the two genome copies in this living fossil had become identical at many places, where the S. paradoxus DNA had been copied onto, and thereby replaced, the baker’s yeast DNA. Even more surprisingly, we found that this living fossil was the direct ancestor of a modern-day baker’s yeast population, the Alpechin yeasts, that today live in the waste-water from olive presses and carry stretches of introgressed S. paradoxus DNA. Irked by this seeming coincidence, we compared the places where the living fossil carried identical DNA in its two genomes to the places where S. paradoxus DNA had introgressed in Alpechin yeasts – and found them to be the same. In other words: the scattered blocks of identical DNA in the living fossil had given rise to the introgressions in its modern descendants. Further experiments shed light on how this had occurred: the scattered blocks of identical DNA allow the living fossil to pair its two genomes and mix their DNA such that the sexual reproduction barrier is overcome and viable offspring produced. The children in turn can mate back to the baker’s yeast, giving rise to grandchildren that carry long stretches of introgressed S. paradoxus DNA. Continuing this process produces genomes that very much look like those of the Alpechin yeasts. This discovery solved the long-standing mystery of how reproductively isolated species can exchange DNA: the secret is simply blocks of identical DNA that allow their two genomes to pair and mix. How do such scattered blocks of identical DNA emerge? Well, that is another mystery waiting for its resolution.

French version:

Comment des organismes sexuellement incompatibles peuvent-ils échanger du matériel génétique ? Ce mystère suscite l’intérêt de la communauté scientifique depuis de nombreuses années. Grâce à la découverte d’une souche de levure à l’architecture génétique ancestrale, nous avons pu mettre en évidence un nouveau mécanisme permettant l’échange de matériel génétique sans avoir recours à la reproduction sexuée.

Lorsque des groupes d’individus sont séparés les uns des autres, ils accumulent progressivement dans leur génome des mutations propres à chaque groupe, dues à des erreurs lors de la réplication de l’ADN. Plus tard, si ces individus issus de groupes distincts se rencontrent, ils peuvent néanmoins se reproduire sexuellement et donner naissance à un hybride, constitué pour moitié de chaque ADN parental. Il arrive que ces hybrides se reproduisent avec des individus provenant d’un des deux groupes originels, engendrant ainsi des descendants dont le génome est enrichi seulement avec l’un des ADN parentaux. Après plusieurs générations de rétrocroisements de ce type, seuls de rares fragments d’ADN issus de l’autre parent originel persistent ; ces fragments sont appelés introgressions. Par exemple, 2% du génome humain d’origine non-Africaine contient de l’ADN de Néandertal résultant de ce processus d’introgression. Les introgressions d’ADN peuvent aussi bien avoir des effets positifs que négatifs, et évoluer au cours du temps. Il a d’ailleurs récemment été constaté que certains gènes directement hérités de Néandertal augmentent significativement la sensibilité au COVID-19, menaçant la santé humaine.

Mystérieusement, nous observons souvent des introgressions chez des espèces génétiquement éloignées qui ne peuvent se reproduire sexuellement l’une avec l’autre. Ce phénomène est longtemps resté une énigme. La levure du boulanger Saccharomyces cerevisiae, champignon unicellulaire indispensable à la production de pain, de bière, de vin, de spiritueux, de café, ou encore de cacao pour ne citer que quelques exemples, est reproductivement isolée de son espère sœur Saccharomyces paradoxus. Malgré le fait que ces deux espèces de levures peuvent s’accoupler et former des hybrides, leur forte divergence génétique (~12%) rend leur descendance majoritairement non-viable, limitant ainsi l’échange de matériel génétique. Cependant, des fragments d’ADN de S. paradoxus ont été retrouvés dans le génome de S. cerevisiae, selon un processus vraisemblablement similaire aux introgressions de Néandertal observées chez l’humain. Comment cela est-il possible alors que les hybrides de S. cerevisiae et S. paradoxus sont stériles ?

Nous avons isolé une souche hybride ancestrale de levure dont la structure génomique n’a pas évolué depuis des centaines de milliers de générations, telle un véritable fossile vivant. Curieusement, les chromosomes homologues de cette levure fossile sont parfaitement identiques en plusieurs endroits où l’ADN de S. paradoxus a complètement remplacé celui de S. cerevisiae. De plus, nous avons démontré que cette levure fossile est l’ancêtre direct d’une autre souche moderne de S. cerevisiae dénommée Alpechin, trouvée dans les eaux usées de la production d’huile d’olive et pourvue d’introgressions de S. paradoxus. Suite à ce constat, nous avons comparé les emplacements où l’ADN de S. paradoxus a complètement remplacé celui de S. cerevisiae chez la levure fossile, avec les zones d’introgressions chez Alpechin, et nous avons constaté qu’elles coïncidaient. En fait, les introgressions de S. paradoxus dans les levures Alpechin résultent directement des fragments maintenus dans la souche ancestrale. Des expériences plus approfondies nous ont permis d’éclaircir les faits : les blocs d’ADN de S. paradoxus conservés dans les chromosomes homologues de la levure fossile lui permettent de recombiner plus efficacement son génome lors de la formation de gamètes pour la reproduction sexuée. Les descendants de la levure fossile ont alors été rétrocroisés successivement avec S. cerevisiae donnant ainsi naissance à des descendants comportant de longs fragments d’introgressions d’ADN de S. paradoxus. A terme, ce scénario aboutit à la formation de génomes très semblables à celui des levures Alpechin.

Cette découverte a ainsi permis d’expliquer comment des espèces reproductivement isolées peuvent échanger du matériel génétique : la formation de blocs d’ADN identiques sur les deux chromosomes homologues permet aux génomes hybrides de se recombiner. Comment ces blocs se forment-ils ? Cela reste encore à élucider.

2020 Research development

« Profiling the Non-genetic Origins of Cancer Drug Resistance »

A group of researchers led by Dr Jérémie Roux, member of the Labex SIGNALIFE team of Prof. Hofman at the Institute for Research on Cancer and Aging (IRCAN) has developed a new method to anticipate how cells respond to cancer treatment

Scientific publication link

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2020.08.019

Canceropole PACA Press release

https://canceropole-paca.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/CP-J.Roux-Cell-Systems-1.pdf

Social networks

https://twitter.com/jrxlab/status/1310614614590324736

https://twitter.com/CanceropolePACA/status/1310862977776717824

https://twitter.com/CellSystemsCP/status/1318938091185295361

https://twitter.com/Nice_Matin/status/1315194191237058562

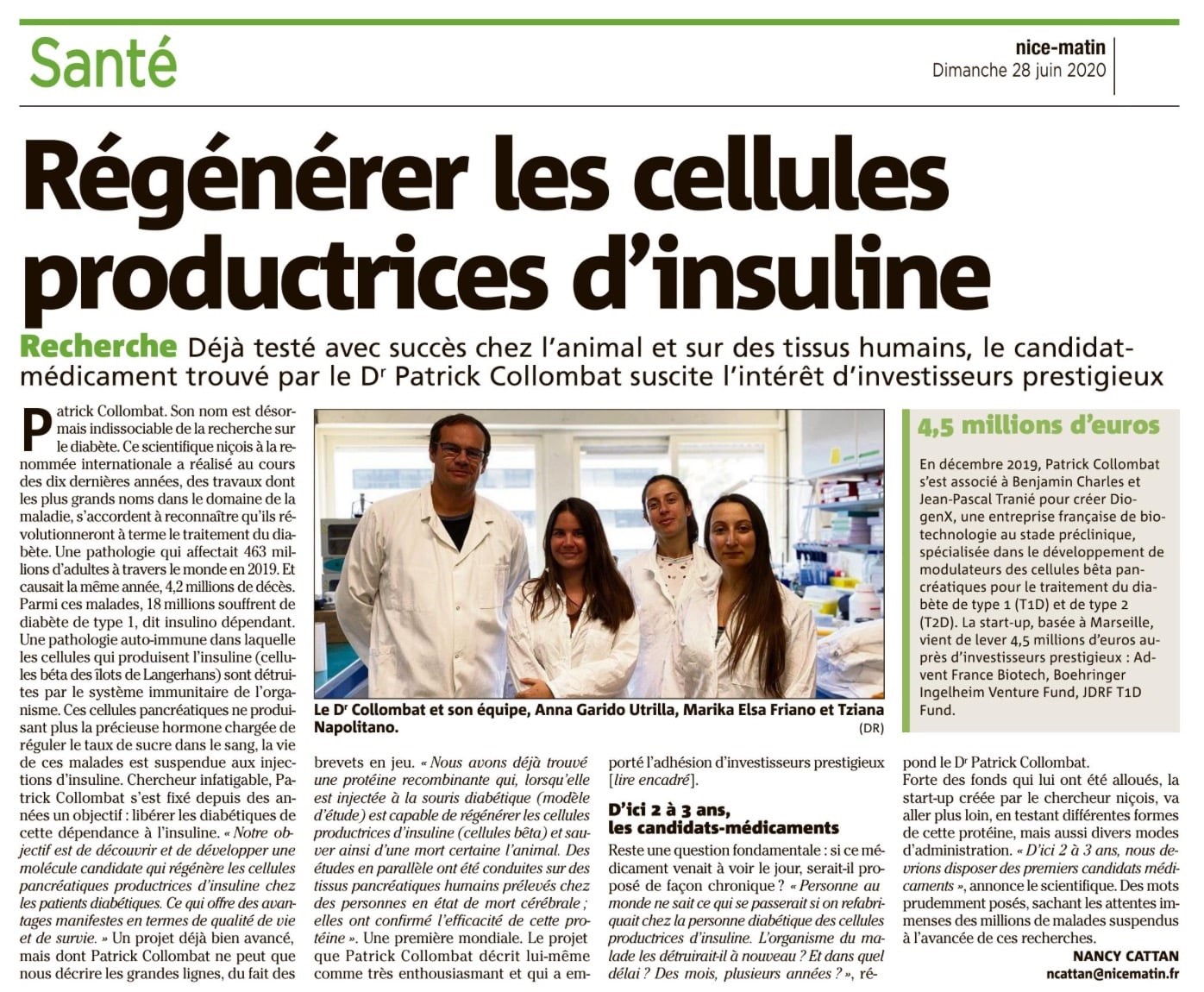

2020 Start up creation

“Regeneration of pancreatic insulin-producing cells”

Dr Patrick Collombat, a Labex SIGNALIFE project leader working in Diabetes Genetics, has recently created a Startup on regeneration of pancreatic insulin-producing cells.

The project involved his research team at the Institut de Biologie Valrose in The University Côte d’Azur, among them 2 former Labex PhD students, Tiziana Napolitano and Serena Silvano. Tiziana is now employed by the Startup DiogenX

2020 Labex Publication

« Novel immune surveillance mechanism of the skin compromised in Xeroderma Pigmentosum patients »

Labex discoveries from a collaboration between Véronique Braud’s (IPMC) and Thierry Magnaldo’s (IRCAN) teams including a PhD Student, Gonçalves-Maia Maria, supported by the Fondation Avenir and the Labex SIGNALIFE

Using an innovative 3-dimensional organotypic skin culture model that contain Natural Killer cells, fibroblasts and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cells, the teams unveiled a key role of CLEC2A, a molecule expressed by fibroblasts, and implicated in the activation of NK cells, leading to the control of SCC invasion. They discovered that this regulation is compromised in patients with Xeroderma Pigmentosum.

Gonçalves-Maia M, Gache Y, Basante M, Cosson E, Salavagione E, Muller M, Bernerd F, Avril MF, Schaub S, Sarasin A, and VM Braud*, T Magnaldo* (*co-authorship). 2020. NK cell and fibroblast-mediated regulation of skin squamous cell carcinoma invasion by CLEC2A is compromised in Xeroderma Pigmentosum. J Invest Dermatol. (IF-6.3) 13:S0022-202X(20)30142-1. PMID: 32061658